Three young scientists have won the grand prize in the Vesuvius Challenge for deciphering previously undecipherable text from the scrolls of Herculaneum.

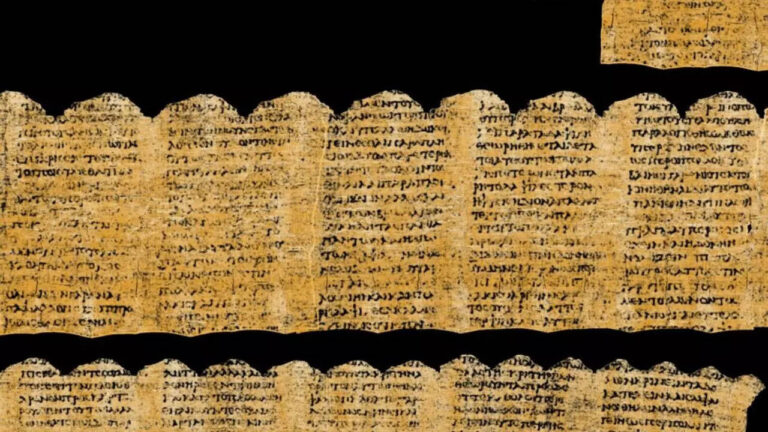

When Vesuvius erupted about 2,000 years ago, more than 1,000 scrolls were buried and covered by volcanic debris. They are located in the library of a Roman villa in the ancient city of Herculaneum and were discovered by a local farmer in the 1800s.

Since then, many people have tried to read the ancient papyrus scrolls, but most attempts ended up destroying the documents. For centuries, the documents remained rolled up, charred, and fragile underground.

The winners, Yusef Nader, Luke Fariter, and Julian Siliger, overcame this challenge by successfully reading four passages without ever opening the scroll.

Win the Vesuvius Challenge

They used machine learning, a type of artificial intelligence, to read ancient Greek texts. Naderi, Fariter and Schillinger have each contributed independently to the Vesuvius Scrolls community and are currently sharing his $700,000 (€650,000) grand prize.

The aim was to decipher four parts of the text, each of at least 140 characters, with at least 85% of the characters “recoverable”, or readable.

Their research uncovered what appears to be an unknown document by the villa’s so-called philosopher, Philodemus.

In the text, Philodemus writes about living a good life through the enjoyment of beauty, music, and food. Researchers say this discovery and those in future documents will provide a “unique window into the classical world.”

How scientists used AI to read the Scrolls of Herculaneum

The scrolls were digitally “opened” using computed tomography (CT) (X-ray photography) and machine learning technology.

First, in late 2023, the prize organizers imaged the scroll at the Diamond Light Source Particle Accelerator near Oxford, UK. This produced a high-resolution CT scan of the scroll.

The scans were then converted into 3D volumes of voxels. Voxels are 3D pixels, similar to the building blocks used in the video game Minecraft.

The second step is known as segmentation. They tracked the crumpled layers of rolled papyrus with a 3D scan. This made it possible to unfold, or flatten, the image.

And the third step was to detect the ink on the papyrus. They used machine learning to identify areas of ink on flat sections of papyrus.

But here’s where it gets really tricky. Machine learning models are not trained to detect ancient Greek characters, optical character recognition (OCR), or other language models.

Instead, they simply detected spots of ink on a CT scan and reconstructed the individual spots by combining them. Where letters appeared, letters were written.

Decades of efforts bear fruit

One of the prize organizers, Brent Shields of the University of Kentucky, has been working on deciphering the Herculaneum Scrolls for decades. Shields used his CT scan for the first time, but found the ink difficult to detect because its density was the same as that written on papyrus.

But development accelerated after Shields, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Nat Friedman and engineer Daniel Gross launched the contest in March 2023.

Within a few months, a breakthrough occurred. Former physicist Casey Handmer noticed a cracked texture in text and called it “crackle.”

Co-winner Fariter, an undergraduate and SpaceX intern, used Handmer’s observations to train a machine learning model that was the first to fully decipher the ancient Greek word for purple, ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ.

By October, Nader, an Egyptian doctoral student living in Berlin, was able to read several paragraphs of text.

Schillinger, a Swiss robotics student, has previously won three awards for his segmentation, which enabled the 3D mapping of papyrus scrolls.

And there’s even more to come in 2024. The next Vesuvius challenge is to read the entire work or scroll by the end of the year.

When Vesuvius erupted about 2,000 years ago, more than 1,000 scrolls were buried and covered by volcanic debris. They are located in the library of a Roman villa in the ancient city of Herculaneum and were discovered by a local farmer in the 1800s.

Since then, many people have tried to read the ancient papyrus scrolls, but most attempts ended up destroying the documents. For centuries, the documents remained rolled up, charred, and fragile underground.

The winners, Yusef Nader, Luke Fariter, and Julian Siliger, overcame this challenge by successfully reading four passages without ever opening the scroll.

Win the Vesuvius Challenge

They used machine learning, a type of artificial intelligence, to read ancient Greek texts. Naderi, Fariter and Schillinger have each contributed independently to the Vesuvius Scrolls community and are currently sharing his $700,000 (€650,000) grand prize.

The aim was to decipher four parts of the text, each of at least 140 characters, with at least 85% of the characters “recoverable”, or readable.

Their research uncovered what appears to be an unknown document by the villa’s so-called philosopher, Philodemus.

Expanding

In the text, Philodemus writes about living a good life through the enjoyment of beauty, music, and food. Researchers say this discovery and those in future documents will provide a “unique window into the classical world.”

How scientists used AI to read the Scrolls of Herculaneum

The scrolls were digitally “opened” using computed tomography (CT) (X-ray photography) and machine learning technology.

First, in late 2023, the prize organizers imaged the scroll at the Diamond Light Source Particle Accelerator near Oxford, UK. This produced a high-resolution CT scan of the scroll.

The scans were then converted into 3D volumes of voxels. Voxels are 3D pixels, similar to the building blocks used in the video game Minecraft.

The second step is known as segmentation. They tracked the crumpled layers of rolled papyrus with a 3D scan. This made it possible to unfold, or flatten, the image.

And the third step was to detect the ink on the papyrus. They used machine learning to identify areas of ink on flat sections of papyrus.

But here’s where it gets really tricky. Machine learning models are not trained to detect ancient Greek characters, optical character recognition (OCR), or other language models.

Instead, they simply detected spots of ink on a CT scan and reconstructed the individual spots by combining them. Where letters appeared, letters were written.

Decades of efforts bear fruit

One of the prize organizers, Brent Shields of the University of Kentucky, has been working on deciphering the Herculaneum Scrolls for decades. Shields used his CT scan for the first time, but found the ink difficult to detect because its density was the same as that written on papyrus.

But development accelerated after Shields, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Nat Friedman and engineer Daniel Gross launched the contest in March 2023.

Within a few months, a breakthrough occurred. Former physicist Casey Handmer noticed a cracked texture in text and called it “crackle.”

Co-winner Fariter, an undergraduate and SpaceX intern, used Handmer’s observations to train a machine learning model that was the first to fully decipher the ancient Greek word for purple, ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ.

By October, Nader, an Egyptian doctoral student living in Berlin, was able to read several paragraphs of text.

Schillinger, a Swiss robotics student, has previously won three awards for his segmentation, which enabled the 3D mapping of papyrus scrolls.

And there’s even more to come in 2024. The next Vesuvius challenge is to read the entire work or scroll by the end of the year.