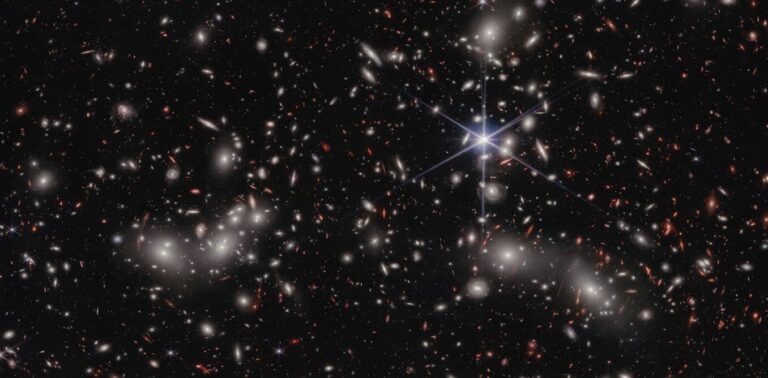

Credits: NASA / ESA / CSA / Ivo Labbe (Swinburne) / Rachel Bezanson (University of Pittsburgh) / Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

× close

Credits: NASA / ESA / CSA / Ivo Labbe (Swinburne) / Rachel Bezanson (University of Pittsburgh) / Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

About 400,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe was a very dark place. The glow of the universe’s explosive birth had cooled, and the universe was filled with dense gas (mostly hydrogen) with no light source.

Slowly, over hundreds of millions of years, gravity forced the gas into clumps, and eventually the clumps grew large enough to ignite. These were the first stars.

Initially, their light did not travel far and much of it was absorbed by the hydrogen gas mist. But as more stars form, enough light is produced to burn off the fog by “reionizing” the gas, dotting the bright spots of light we see today. A transparent universe was formed.

But which stars, exactly, produced the light that ended the Dark Ages and sparked this so-called “age of reionization”? In a study published in the journal Nature, we discovered that a giant galaxy I used the group as a magnifying glass to observe faint relics of this era. They discovered that stars in small, faint dwarf galaxies are likely involved in this cosmic-scale change.

What brought the Dark Ages to an end?

Most astronomers already agreed that galaxies were the primary reionizing forces in the universe, but it was not clear how they did it. We know that stars within a galaxy must produce large amounts of ionizing photons, but these photons must escape from the dust and gas inside that galaxy in order to ionize hydrogen in intergalactic space. there is.

It’s not clear what types of galaxies can produce and emit enough photons to accomplish the task. (And in fact, some believe that more exotic objects, such as large black holes, may be responsible.)

There are two camps among proponents of the galaxy theory.

The first believes that a large, massive galaxy produced the ionizing photons. There weren’t many of these galaxies in the early universe, but each produced a large amount of light. Therefore, if a certain portion of that light managed to escape, it might have been enough to re-ionize the universe.

The second camp believes it is better to ignore giant galaxies and focus on the vast number of much smaller galaxies that exist in the early universe. Each of these would have produced far less ionizing light, but given the weight of their numbers, they could have triggered an epoch of reionization.

Magnifying glass 4 million light years wide

Trying to study the early universe is extremely difficult. Giant galaxies are rare and therefore difficult to find. Small galaxies are more common, but they are very faint, making it difficult (and expensive) to obtain high-quality data.

We wanted to observe some of the faintest galaxies around us, so we used a huge group of galaxies called the Pandora cluster as a magnifying glass. The cluster’s huge mass distorts space and time, amplifying light from objects behind it.

As part of the UNCOVER program, we used the James Webb Space Telescope to observe enlarged infrared images of faint galaxies behind the Pandora star cluster.

We first looked at a number of different galaxies and then selected a few particularly distant (and therefore ancient) galaxies to study further. (Because this kind of detailed examination is expensive, only eight galaxies could be observed in greater detail.)

The bright glow of hydrogen

We selected several light sources that were about 0.5% of the Milky Way’s brightness at the time and saw the telltale glow of ionized hydrogen. These galaxies are so faint that they could only be seen thanks to the magnifying effect of the Pandora star cluster.

Our observations confirm that these small galaxies existed in the very early universe. What’s more, we found that it produces about four times more ionizing light than we would consider “normal.” This is the highest we’ve predicted based on our understanding of how early stars formed.

These galaxies produced so much ionizing light that only a small portion of it would have needed to escape to re-ionize the universe.

Previously, it was thought that about 20% of all ionizing photons would have to escape from these small galaxies for them to become the dominant source of reionization. Our new data suggests that even 5% is enough. This corresponds to a fraction of the ionizing photons emitted by modern galaxies.

Therefore, we can now say with confidence that these small galaxies may have played a very large role during the era of reionization. However, our study was based only on eight galaxies, all close to a single line of sight. You need to look at different parts of the sky to see the results.

We are planning new observations to target other large galaxy clusters elsewhere in the universe to find and test even more enlarged faint galaxies. If all goes well, we’ll have some answers within a few years.