The Department of Veterans Affairs has recouped billions of dollars that were given to countless veterans as an incentive to leave the military when the military needed to be downsized, according to new data obtained by NBC News.

Over the past 12 fiscal years, disabled veterans have been ordered to pay back about $3 billion in special severance pay, a lump-sum incentive given when the U.S. has to reduce active-duty military personnel or release minor injured service members, according to the data.

According to the VA, about 122,000 veterans have repaid more than $2.5 billion since fiscal year 2013, the first year the department shared the data, but about $364 million remains unpaid.

“It felt like there was never any light at the end of the tunnel,” said Damon Byrd, who is struggling to pay back about $74,000 in retirement benefits he received when he left the Army in 2015.

The VA said it is legally obligated to collect retirement benefits before eligible veterans can start receiving disability benefits because a little-known federal law bars veterans from receiving both benefits, NBC News previously reported.

The little-known law has plunged many disabled veterans into financial and emotional despair since Congress approved it in 1949. About a dozen experts in military law and veterans policy said they didn’t know enough to comment.

“I felt like I was used and abused.”

Salahuddin Majeed, retired military officer

Byrd, 54, said he and his wife had to move out of their rental home in Haslett, Texas, to live with their daughter in 2021 after the VA began garnishing his disability benefits of more than $2,400 a month until he repays his retirement benefits.

“We were struggling to make ends meet,” said Byrd, who was diagnosed with service-related bladder cancer and post-traumatic stress disorder. “That was bad enough, but I was having mental health issues even before I lost my income.”

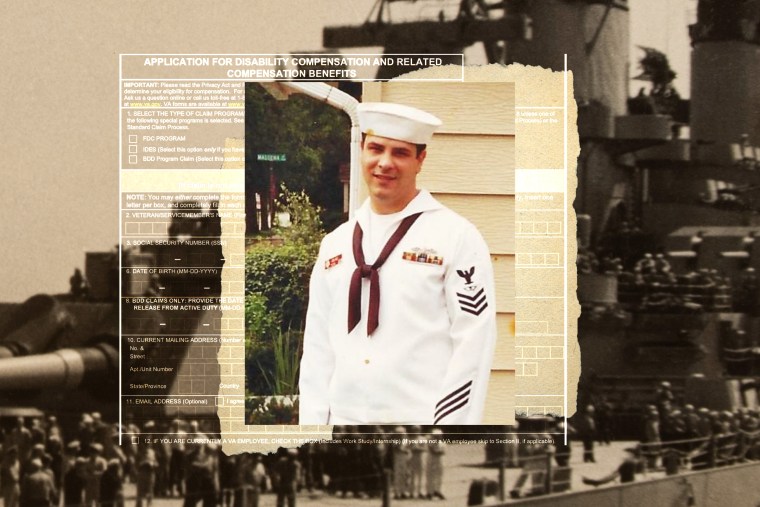

Salahuddin Majeed, a 73-year-old Army veteran, still remembers the anguish he felt when the VA told him he had to repay the special retirement benefits he received in 1992.

He said the payout of about $30,000 before taxes was one of his proudest moments at the time.

“I received my payment and I read the check to my kids,” Majeed said. “I said, ‘We’ll never see this amount of money again in our lifetimes.'”

Majeed said he used most of the money toward a down payment on a house for his growing family. Two years later, the VA told him he had to pay back the entire incentive in order to receive disability benefits.

“I was depressed,” he said, adding that he was prescribed antidepressants for the first time. “I felt like I’d been used and abused.”

Veterans launch legal battle

According to the Congressional Research Service, for the past 75 years, Congress has prohibited military members from receiving two government benefits at the same time.

When Congress authorized disability retirement benefits in 1949 — a special lump-sum payment given to military personnel who left active duty with a minor physical disability — it specified that the payments had to be recouped through the Department of Veterans Affairs’ disability benefits, the research group said.

A House report accompanying the bill said the provision was “fully justified given the sums involved,” according to the Congressional Research Service.

The justification for the compensation provision continued into the 1990s when other forms of special retirement benefits unrelated to disability were approved. These benefits, including the Special Severance Pay (SSB), were designed to allow the Department of Defense to control the size of its force.

Advocates say the compensation law shouldn’t apply in these cases and that the law deprives veterans of earned benefits that shouldn’t be tied to them financially.

“They are two separate chunks of money.”

Attorney Marquis Barefield

While retirement benefits are based on a service member’s military record and are calculated by the number of years they served on active duty, disability benefits relate only to illnesses or injuries suffered while in the military, said Marquis Barefield, deputy director of national legislative affairs for DAV, an advocacy group formerly known as the Disabled American Veterans Association.

“These two payments have nothing to do with each other,” Barefield said. “They’re two separate pieces of money.”

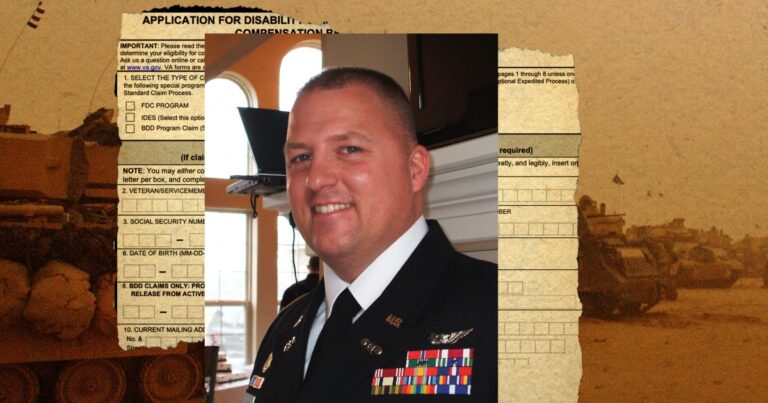

Navy veteran John Collage, 62, is currently fighting the case in the Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, arguing that the VA complicated the law to justify recovering his SSB benefits.

VA spokesman Terrence Hayes said the SSB was authorized by 10 U.S.C. § 1174a. Hayes said the SSB amount must be recovered from VA disability benefits under the provisions of the law that apply to § 1174a under Section 3.

Collage said he believes the VA is mistakenly subjecting many disabled veterans to provisions related to retirement benefits rather than disability.

“They’re wrong,” he said. “They shouldn’t have received this money.”

Collage, a survivor of the 1989 explosion of the USS Iowa, which killed 47 people, said he received about $23,000 after taxes when he collected SSB benefits in 1992. After applying for disability benefits from the VA for PTSD and other symptoms, he was told to pay it back in 2017. The VA is withholding about $370 each month, Collage said.

“They’re scamming tens of thousands of veterans out of their money,” Collage said.

The VA said it cannot comment on individual appeals.In a court motion this month, lawyers for VA Secretary Dennis McDonough asked for an extension to the deadline to respond to Collage’s lawsuit until Sept. 16, citing his workload, court records show.

Majeed, a 73-year-old army veteran, also a recipient of SSB benefits, had similarly fought against compensation in the Veterans Claims Appeal Tribunal around 30 years ago, but ultimately lost.

In 1998, the Veterans Affairs Review Board determined, among other things, that “his VA disability compensation is subject to recovery of retirement benefits.”

“They were refusing to give me what I felt was rightfully my own,” Majeed said.

“Legal reform is needed”

Disabled veterans have long had problems with the law, and their concerns led Congress to mandate a study of how compensation has affected veterans.

In 2022, the nonprofit research group RAND Corp., which conducted the study, found that the law forced at least 79,000 veterans to pay back various types of retirement benefits between 2013 and 2020.

The actual number of veterans affected and the total amount recovered are likely much higher, but the researchers note in their study that data is limited by major changes to the VA’s system in 2013, resulting in as much as 60 years of missing data.

Despite Congress’ historic efforts decades ago to solidify the compensation, at least one current lawmaker now wants to overturn it: In 2022, Rep. Ruben Gallego, a Democrat from Arizona, introduced a bill to eliminate the compensation for disability benefits.

“We need a change in the law,” Gallego said. While the measure has bipartisan support, it is moving slowly on the legislation because of its cost, Gallego said.

Meanwhile, veterans who say they were unaware of the law when they received their benefits are being forced to make significant and often painful life changes.

When Mr. Byrd, an Army veteran who was forced to live with his daughter, received his forced severance pay of about $74,000, he assumed it was the same as a severance pay he would have received from a civilian layoff and used the money to build a new life.

Byrd moved from Missouri to Texas, paid off his debts, and after trying various jobs, landed a job as a high school math teacher at a school near his home.

“It was enormous,” he said of the money’s impact. “We lived comfortably for a few years.”

Six years later, the VA sent him a letter saying he should not have received both his disability and retirement benefits without penalty.

“I sacrificed myself for almost 18 years to do everything I could to serve my country,” said Byrd, a senior officer who served two tours in Iraq, including during the invasion. “It was like a stab in the back.”