- Fourteen states have adopted comprehensive data protection laws, most of which are expected to go into effect within the next two years.

- Of these laws, only the California Privacy Rights Act applies to human resources data.

- Nevertheless, employment advisors and human resources professionals are involved in helping organizations comply with the extensive responsibilities these laws impose.

- States have also proposed and enacted smaller laws applicable to HR data.

The Governor signed the New Jersey Privacy Act on January 16, 2024, making New Jersey the 14th state in the United States to pass a comprehensive data protection law. With this accelerating legislative trend, employment advisors and human resources professionals may be concerned about how to prepare for the burdensome privacy obligations these laws impose. The good news for employers is that most of these laws exempt data collected about employees, job applicants, and other “human resources data.” Nevertheless, employers are not completely exempt from the burden of compliance. The most demanding of these new laws, the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), applies fully to human resources data, and some proposed state laws also target this data. Additionally, while data protection laws in states other than California do not apply to HR data, HR departments play a role in the process of complying with these laws.

Overview of the new data protection law

Data protection is a broad concept. The basic idea is to protect personal information, generally defined as personally identifiable information, and to provide some degree of control over the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information. A wide range of data protection laws, from common privacy laws to data breach notification laws, have protected Americans for more than a century. The new state data protection law is novel only in the following ways: comprehensive Data protection law.

Traditionally, data protection laws in the United States have been sector-specific laws that focus on specific hazards or industries, such as HIPAA for the healthcare industry. In contrast, comprehensive data protection laws cover most personal information, not just narrow categories, and apply to businesses in all industries. Additionally, these comprehensive laws impose broad responsibilities on covered organizations to protect personal information. Like many existing laws, these laws require the introduction or maintenance of safeguards to ensure data security. They also require companies to provide individuals with detailed notice (usually through an online privacy policy) at the point of collection about the personal information they collect, the purposes for which it will be used, disclosures, and other aspects. Additionally, companies must only process personal information in the manner described in such notice. Data protection laws provide individuals with enumerated rights regarding their personal information, most commonly the right to access, rectify, delete, and to opt-out of targeted advertising or sales of their personal information. Organizations subject to these laws must also extend these obligations to third-party service providers (“processors”) that receive personal information pursuant to specific vendor contract requirements.

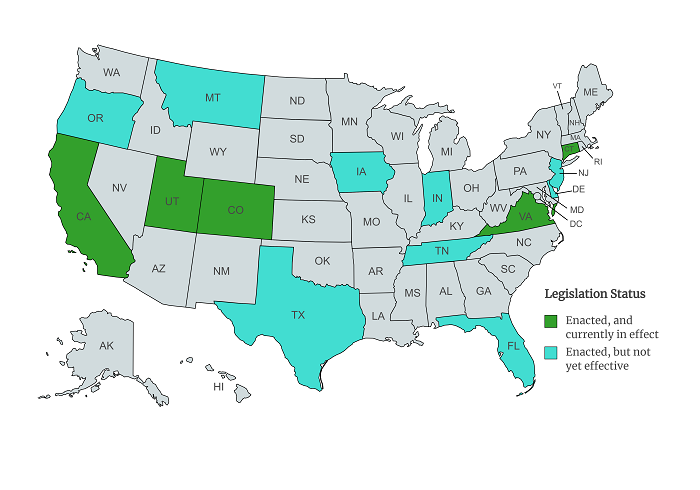

The following states currently have comprehensive data protection laws in place, as shown in the map below:

- California

- colorado

- connecticut

- Delaware (effective January 1, 2025)

- Florida (effective July 1, 2024)

- Indiana (effective January 1, 2026)

- Iowa (effective January 1, 2025)

- Montana (effective October 1, 2024)

- New Jersey (effective January 1, 2025)

- Oregon (effective July 1, 2024)

- Tennessee (effective January 1, 2025)

- Texas (effective July 1, 2024)

- Utah

- Virginia

With the exception of California law, these laws do not apply to human resources data

These new state data protection laws apply to the processing of Personal Information or Personal Data of Consumers residing in the applicable states. With the exception of California, each state explicitly excludes human resources data, or information about individuals who: (1) Employees. (2) Job seekers. (3) Independent Contractors. (4) as a beneficiary of someone in terms of employment; or (5) other employment-related qualifications.

For example, the Colorado Privacy Act defines: consumer As a Colorado resident “acting only in a personal or household context” rather than “as a beneficiary of an employment context, a job applicant, or someone acting in an employment context.”1 Similarly, the Delaware Personal Data Privacy Act and the Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act each provide that: , which provides that certain types of data are exempt from the scope of the law. This data is used within the context of the role, as well as for emergency communication purposes or to administer benefits to dependents and other beneficiaries of employee benefit plans. It also includes data.2

In contrast, as noted above, California’s CPRA generally applies to any personally identifiable information of California residents, including personnel data. Employers familiar with the California Consumer Privacy Act, the predecessor to the CPRA, will know that the law exempts human resources data from nearly all requirements. However, effective January 1, 2023, the CPRA removed that exemption and created additional compliance obligations for California commercial employers who: (1) His annual total revenue exceeds $25 million. (2) buy, sell, or share the personal information of more than 100,000 California residents or households; or (3) derives 50% or more of its annual revenue from the sale or sharing of California residents’ personal information. Eligible California employers must provide detailed privacy notices to California applicants. Employees and officers and their dependents, emergency contacts, and beneficiaries. and independent contractors and directors. You must also include CPRA-compliant provisions in your contracts with California personal information service providers. To respond to requests for information, deletion, and correction. There are requirements such as erasing personal information when it is no longer needed.3 Notably, unlike nearly all of the other state data protection laws mentioned above, the CPRA’s requirements apply equally to “commercial” information (In other words., business contact data).

State data protection laws other than CPRA remain relevant to human resources departments

Compared to the CPRA, other states’ data protection laws generally have much higher standards of enforcement. In most of these laws, the law determines the purposes and means of processing of personal information, a “controller” operating within the state, or providing services or products intended for residents of the state; and only applies to any of the following:

- Manage or process the personal information of 100,000 or more State residents in a consumer capacity during a calendar year.or

- Manage or process the personal information of at least 25,000 state residents in their capacity as consumers and receive a percentage of the revenue from the sale of their personal information.Four

There are also some exceptions. For example, Delaware, Montana, and Tennessee have set standards for managing or processing personal information at 35,000, 50,000, and 175,000 state consumers annually, respectively.Five Florida’s law applies only to organizations with annual global revenues of more than $1 billion.6 In sharp contrast to other states’ high standards, Texas law applies to any business doing business in Texas that does not meet the U.S. Small Business Administration’s definition of a “small business.”7

This means that, with the exception of Texas, only very large companies, or those whose products or services involve the collection of large amounts of personal information, may be directly subject to these laws as controllers. However, even companies that do not meet the thresholds may be subject to liability under these laws when they process personal information on behalf of a controller in a processor role. First, the law requires processors to maintain reasonable data security of personal information, to assist in responding to requests from consumers to exercise their rights, and to ensure that controllers demonstrate compliance with the law. Requires controllers to assist them in directly complying with this law, including by providing the information required by the law. Legislation. Second, these data protection laws require controllers to impose contractual obligations on processors. These obligations include processing personal information only in accordance with the controller’s instructions, permitting or cooperating with controller audits and inspections, and ensuring that all employees handling personal information are subject to a “duty of confidentiality.” This includes:

Therefore, state data protection laws other than the CPRA remain relevant to employment advisors and human resources professionals, even though they do not apply to human resources data. Due to the comprehensive nature of this law, it is important that anyone handling personal information covered by it has at least a basic understanding of the rules and how to comply with them. As managers of employee policies, human resources departments and employment advisors will help develop and implement policies and procedures for employees regarding the handling of personal information subject to data protection requirements. Human resources professionals may also be involved in training employees to comply with new regulations. If some employees inevitably violate the policy, the human resources department must conduct an investigation and take disciplinary action.

Proposed data protection law could target human resources data

Dozens of privacy bills introduced at both the state and federal levels demonstrate the growing interest in protecting privacy. Many are comprehensive data protection bills, which continue to be introduced in each legislative cycle.8 Although many of these bills do not follow the model of California’s CPRA, some states have adopted laws that fully apply to HR data, such as LD 1977 (the “Data Privacy and Protection Act”), currently before the Maine Legislature. We are proposing a bill to do so. Given the large number of pending bills, further legislation directly applying to HR data may soon be enacted.

Importantly, comprehensive data protection legislation is just one category of pending privacy legislation. States continue to propose and pass smaller privacy laws applicable to HR data, including laws regarding electronic monitoring and records, data security, location tracking, biometric data protection, and related items.9 Such laws do not individually qualify as comprehensive data protection laws, but together they constitute a legal framework similar to comprehensive data protection laws. As a result, as this legislative trend continues, data protection concerns are almost certain to occupy more of the time and attention of human resources professionals and employment lawyers.

footnote

1 Colorado Pastoral Statistics § 6-1-1303(6).

2 Del. Code Tit. 6 § 12D-103(c)(11); Indian Law 24-15-1-2(13).

3 For more information about the application of the CPRA and related compliance requirements for California employers, including articles, podcasts, recorded webinars, and more, please visit www.littler.com/CPRA.

Four Colorado Pastoral Statistics § 6-1-1304(1); Connecticut General Statistics §42-516; Indian Code § 24-15-1-1(a); Iowa Code § 715D.2(1); ORS § __ .__ (SB 619 §2(1)); Utah Code § 13-61-102(1); Va. Code § 59.1-576(A). Although not yet enacted as of this article’s publication, New Jersey’s comprehensive data protection bill includes identical standards of applicability. look S332 § 2, 220 Leg. (New Jersey 2024).

Five Del. Code Tit. 6 § 12D-103(a); Mont. Code § 30-14-__ (SB0384 § 3); Tenn. Code § 47-18-3202.

6 Several other standards apply, including Florida §§ 501.702(9) for operators of “consumer smart speakers” and “app stores or digital distribution platforms.” Same as above.

7 tex bus. &Communications Code §541.002(a).

8 Examples include New Hampshire Senate Bill 255, Wisconsin Assembly Bill 466, and HR 2701 in the U.S. Congress.

9 For example, look at Zoe Argento, Frances Kenny, and Spencer Soucy. New Jersey joins the trend of increasing privacy protections for employee locations, Littler Insight (March 30, 2022). and Philip Gordon, Joseph Flanagan, Spencer Soucy, Turn on the lights: New York state mandates transparency in electronic surveillanceLittler Insight (November 11, 2021).