The problem isn’t that the data is bad — in fact, most of it seems to be heading in the right direction — but that the Fed is relying too heavily on it to make decisions, said Tom Lee, managing partner at Fundstrat Global Advisors. CNBC.

Lee argued that by doing so, the Fed was delaying decisions needed to curb inflation and now risks repeating the same mistake. “Now the Fed is missing the turning point for a soft landing,” he said.

A soft landing is now more likely, but still not certain, according to Lee.[The] “The key is for the Fed to move away from data dependency, because that’s what caused it to miss the turnaround in inflation,” he said.

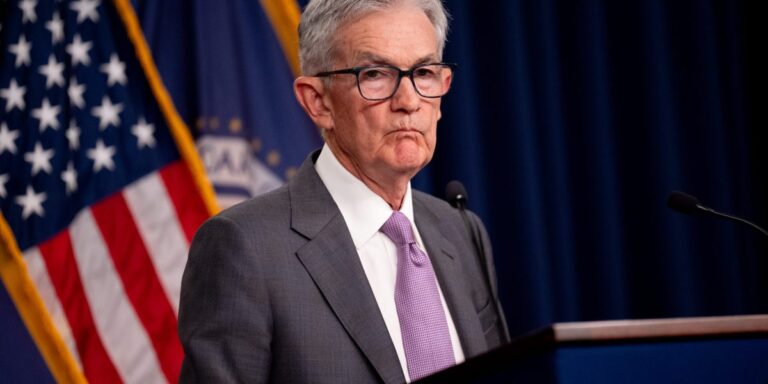

Lee’s comments stand in stark contrast to the Fed’s data-dependent approach, with Chairman Jerome Powell repeatedly saying he won’t cut interest rates until he has more “good data.”

It appears Powell finally got his wish: Fed officials “judged that recent data have increased their confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent,” according to minutes of the most recent Fed meeting released Wednesday.

But the Fed hasn’t always been so data-focused. In fact, the idea that they should be data-focused is relatively new in the history of the Fed, starting around the mid-2010s. Essentially, this means that the Fed will not commit to a specific course of action in terms of lowering interest rates or curbing inflation. Instead, the Fed will base its decisions on certain market indicators that point to the fact that prices are actually falling. In the past, the Fed has sometimes made interest rate decisions based on pre-determined timelines. For example, in August 2011, the Fed publicly stated that it expected interest rates to remain at zero percent “until at least mid-2013.”

Critics say the Fed’s data-dependent approach sometimes puts it at a reactive stage, as it waits for data to emerge rather than predicting the economy’s direction. They also say over-reliance on data doesn’t help when the data is giving conflicting signals. This has been especially evident over the past year, when inflation continued to rise but consumers continued to spend. Typically, the opposite happens during periods of rising prices. (Though consumers have been more frugal than they were earlier this year.)

According to James Bullard, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, relying on data properly requires scrutinizing everything, recognizing what’s important and separating it from what’s not.

“Every observation about the economy (e.g., a GDP report or a jobs report) contains a certain amount of signal and a certain amount of noise,” Bullard, a proponent of data reliance, wrote in a blog post in 2016. “The art of policymaking involves distinguishing between signal and noise.”

With the economy teetering between a miraculous soft landing and a recession, it’s crucial now that the Fed has its finger on the pulse. Over the past two years, the Fed has been able to bring inflation down without a recession or a spike in unemployment. But missing the right time to cut rates now could negate all that effort. At this point, economists and investors consider a September rate cut almost certain, with a higher probability of coming just a second before the end of the year.

Mr. Lee is already considering further rate cuts. “At least from a market perspective, more aggressive rate cuts would make sense,” he said.