When EOS first launched in 2015, it relied mainly on imagery from multiple satellites, particularly the European Union’s Sentinel-2. But Sentinel-2’s maximum resolution was 10 meters, limiting its use in spotting problems on small farms, says Yevheny Marchenko, the company’s sales team leader.

So last year, the company launched EOS SAT-1, a satellite designed and operated specifically for agriculture. Fees for the crop-monitoring platform currently start at $1.90 per hectare per year for small farms, decreasing as farm size increases. (Farmers who can afford it are adopting drones and other related technologies, but drones are quite expensive to maintain and expand, Marchenko says.)

In many developing countries, agriculture is hampered by a lack of data. For centuries, farmers have relied on indigenous wisdom rooted in experience and hope, says Daramola John, a professor of agriculture and agricultural technology at Bellus University of Technology in southwestern Nigeria. “Africa is lagging far behind in the race to modernize agriculture,” he says. “And many farmers are suffering huge losses because of it.”

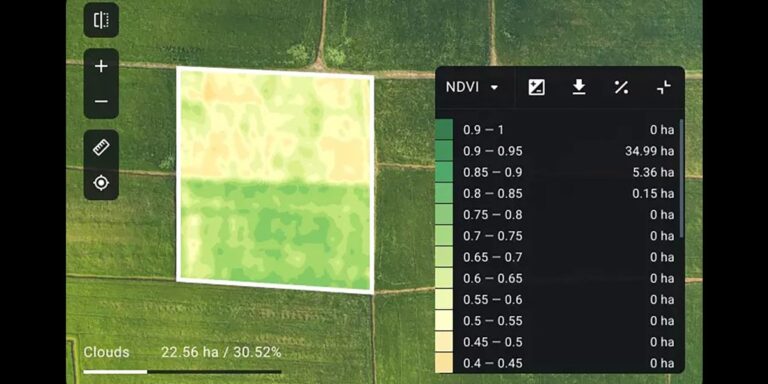

As the new planting season began in spring 2023, Tope’s company, Carmi Agro Foods, had mapped farm boundaries with GPS-enabled software. It had also set up the EOS crop monitoring platform. Tope used the platform to determine proper spacing between stalks and seeds. The rigors and risks of manual monitoring were gone. Field monitors only had to peek at their phones to know when and where specific locations needed attention across different farms. Weed emergence could be tracked quickly and efficiently.

The technology is also gaining popularity among farmers in other parts of Nigeria and other parts of Africa: More than 242,000 people across Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, the United States and Europe are using the EOS crop monitoring platform. In 2023 alone, more than 53,000 farmers have subscribed to the service.