Smartphones have a scaling problem: specifically, the radio frequency (RF) filters that all phones, and all wireless devices in general, use to extract information from isolated wireless signals are too large, too flat, and too numerous — without these filters, wireless communication just wouldn’t work.

“They’re literally the entire backbone of the wireless system,” says Roozbeh Tabrizian, a researcher at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

So Tabrizian and other researchers at the University of Florida developed an alternative, three-dimensional RF filter that could save space in smartphones and IoT devices. If the 3D filter could one day replace stacks of bulky two-dimensional filters, freeing up space for other components like batteries. It could also make it easier to introduce wireless communication into terahertz frequencies, a key spectral range being investigated for 6G cellular technology.

“In the near future, trillions of devices will be connected to wireless networks, and new spectrum will be needed. All you need are different frequencies and different filters.” —Roozbeh Tabrizian, University of Florida

The filters used in wireless devices today are called planar piezoelectric resonators. Each resonator has a different thickness, and the specific thickness of a resonator is directly tied to the band of wireless frequencies that the resonator responds to. Wireless devices that rely on multiple spectral bands (which are becoming more and more common today) increasingly require these planar resonators.

But as wireless signals have proliferated and the spectrum they depend on has expanded, planar resonator technology has revealed some weaknesses. One is that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to make filters thin enough to cover the new spectral regions that wireless researchers are interested in exploiting for next-generation communications. Another is space: It’s proving increasingly difficult to pack all the necessary signal filters into a device.

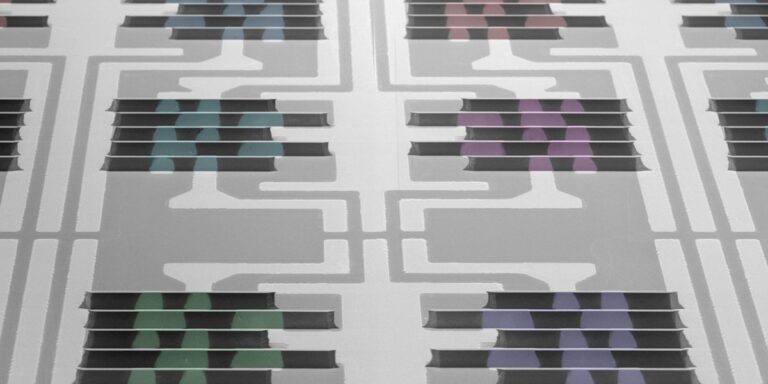

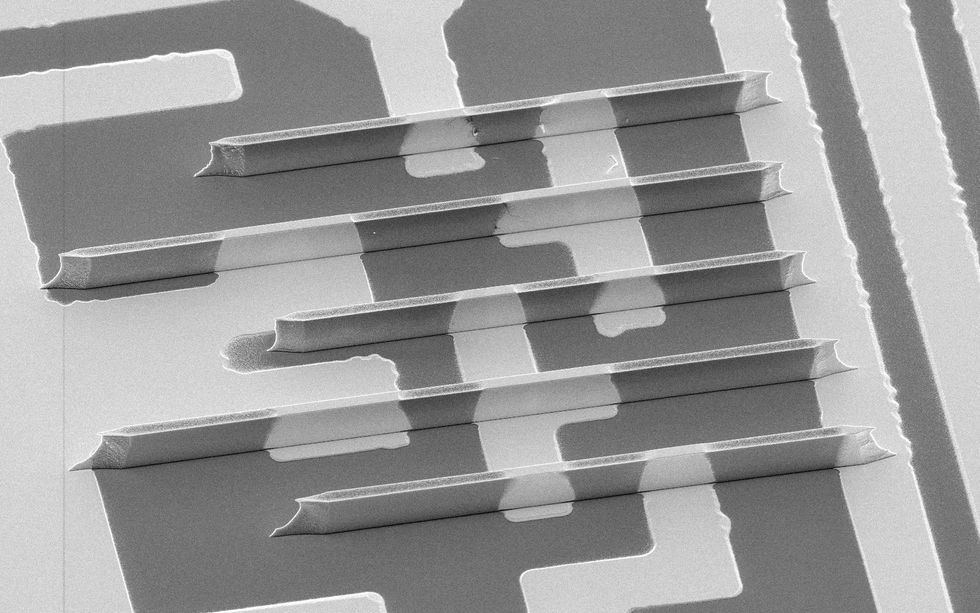

The vertical fins of the ferroelectric-gate fin resonator can be constructed in the same way as FinFET semiconductors.Faysal Hakim/Roozbeh Tabrian/University of Florida

The vertical fins of the ferroelectric-gate fin resonator can be constructed in the same way as FinFET semiconductors.Faysal Hakim/Roozbeh Tabrian/University of Florida

“In the near future, we’re going to have trillions of devices connected to wireless networks, and we’re going to need new spectrum. All we need is different frequencies and different filters,” Tabrizian said. “You open up your phone, and there are five or six specific frequencies, and that’s it. Five or six frequencies just can’t handle it. It’s like having five or six roads and trying to handle the traffic of a city of 10 million people.”

In making the switch to 3D filters, Tabrizian and his colleagues took inspiration from another industry that made the leap into the third dimension: semiconductors. Just as the industry was finally hitting a dead end in its relentless drive to shrink chip sizes, a new approach that suspends electronic channels above the semiconductor substrate breathed new life into Moore’s Law. This chip design is called FinFET (short for “fin field-effect transistor,” with “fin” referring to the shark-fin-like vertical electronic channel).

“The fact that you can vary the width of the fins goes a long way in significantly improving the performance of the technology.” —Roozbeh Tabrizian, University of Florida

“We were definitely inspired [by FinFETS]”The change from planar to fin transistors is to reduce the effective size of the transistor while maintaining the same active area,” Tabrizian said.

Despite taking inspiration from FinFETs, Tabrizian said there are some fundamental differences in how the RF filter’s vertical fins are implemented compared to chips: “If you think about FinFETs, all of the fins are roughly the same width. The dimensions of the fins haven’t changed.”

That’s not the case with filters, which need fins of different widths so that each fin of the filter can be tuned to a different frequency, allowing one 3D filter to process multiple spectral bands. “The fact that we can vary the width of the fins is really useful for dramatically improving the performance of this technology,” Tabrizian says.

Tabrizian’s group has already fabricated several three-dimensional filters called ferroelectric-gate fin (FGF) resonators that cover frequencies from 3 to 28 gigahertz. They have also built a spectrum processor consisting of six integrated FGF resonators that cover frequencies from 9 to 12 GHz. (By comparison, 5G’s coveted mid-band spectrum is between 1 and 6 GHz.) The researchers published their findings in January. Nature Electronics.

The development of 3D filters is still in its early stages, and Tabrizian acknowledges that there is a long way to go. But again, drawing inspiration from FinFETs, Tabrizian sees a clear path forward for the development of FGF resonators. “The good news is that by looking at FinFET technology, we can already guess what many of these challenges are,” Tabrizian says.

Integrating FGF resonators into commercial devices in the future will require solving several manufacturing issues, such as how to increase the density of the filter’s fins and improve the electrical contacts. “Fortunately, FinFETs already solve a lot of these issues, so the manufacturing part is already addressed,” Tabrizian says.

One thing the research group is already working on is a process design kit (PDK) for FGF resonators. PDKs are common in the semiconductor industry and act as a kind of guidebook for designers to manufacture chips based on components detailed by chip foundries.

Tabrizian also sees great potential for future manufacturing to integrate FGF resonators and semiconductors into one component, given the similarities in design and manufacturing: “It’s human innovation and creativity that will come up with new types of architectures, which could revolutionize the way we think about resonators, filters and transistors.”

From an article on your site

Related articles from around the web